Trade Wins and Trade Winds

Exploring the economic impact of recent trade agreements.

Progress — and lack of progress — in negotiating, signing and approving trade agreements has taken center stage in the mainstream media for the past couple years.

How do these headlines connect to the bottom line for U.S. soybean farmers? Do they change the industry outlook?

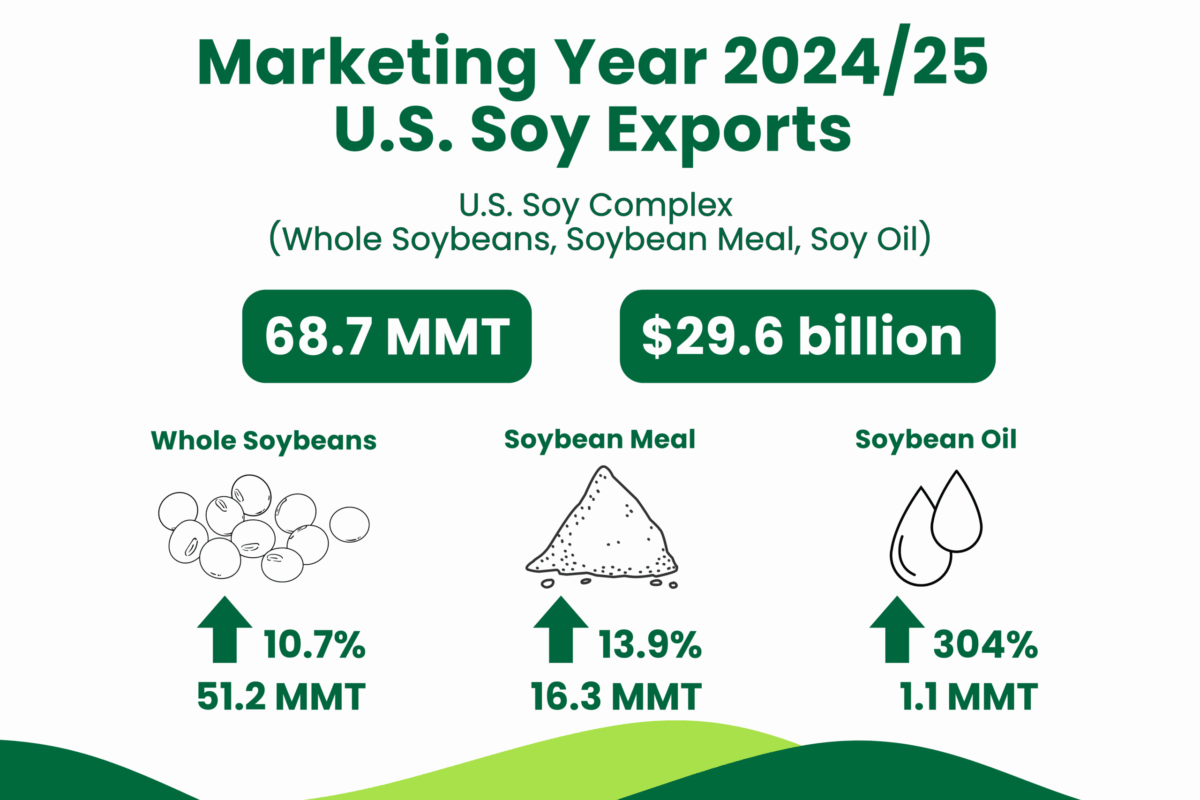

“Approximately 60% of the soy grown in the U.S. is exported to international markets,” says Jim Sutter, CEO of the U.S. Soybean Export Council. “U.S. soybean farmers depend on exports.”

“Trade agreements are critically important to soybean farmers,” agrees Brian Kuehl, director of government affairs for K·Coe Isom, a food and agriculture consulting and accounting firm. “Prices for all soybeans, both those exported and those used domestically, depend on exports because of that volume. Trade agreements are tools needed to export soybeans.”

Kuehl notes the importance of trade agreements for soybean exports extends beyond farmers to the rural economies they support.

“Agriculture is the lifeblood of our rural communities,” he says. “When farmers are hurting, main street businesses, equipment dealers and schools all feel the pain, too.”

Phase One Agreement with China

The trade situation with China, including tariffs, caused U.S. soybeans to no longer be price-competitive with other regions. Kuehl and Sutter both acknowledge this situation caused uncertainty and challenges for U.S. farmers.

“We welcomed the news that the U.S. and China have signed a Phase One trade deal,” says Sutter. “The deal includes commitments by China to substantially increase imports of soybeans. We are ready to meet this demand while maintaining delivery of U.S. soy products to other regions. It has the potential to be beneficial for both U.S. Soy and our partners in China. Finer details, such as the exact value of specific farm purchases, have not been released.”

According to Sutter, China agreed to buy U.S. goods over a two-year period that include nearly doubling agricultural purchases to $40 billion.

Despite that promising news, Kuehl points out challenges to overcome as the Phase One agreement with China unfolds.

“The agreement with China includes stipulations about market conditions and commercial considerations,” he explains. “Because Chinese tariffs on soybeans remain in place, U.S. soy is still not fully cost-competitive. We don’t know how that will impact their side of the agreement.”

But Kuehl believes other market factors impacting China will also have significant influence on the execution of the Phase One deal.

African swine fever remains a critical factor in China’s soybean demand. China relied on soybean imports to feed the world’s largest pig herd. Although the accuracy of reporting is uncertain, Global AgriTrends estimates about two-thirds of China’s herd has been lost, and that the disease continues to spread.

“China’s pork production is unlikely to reach previous levels any time soon,” Kuehl says. “That will impact their near-term soybean demand.”

The recent COVID-19 outbreak adds even more uncertainty. Ports and factories shut down weeks longer than planned following Lunar New Year celebrations at the end of January in response to quarantines and efforts to contain the spread of the virus. This disrupted many industry supply chains, including technology, autos, textiles and food supply. Reports note disruptions to transportation and lockdown measures could prevent food supplies, including the livestock that consume soybeans, from reaching large cities.

Since the beginning of February, the U.S. government predicted it will likely take longer than expected to get the orders from the Phase One agreement with China, including ag commodities, because of the illness. That still seems likely. However, as of early April, China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs claimed soybean imports had not been affected by the spread of COVID-19.

The reality is that China purchased twice as many U.S. soybeans in the first quarter of 2020 as it did in the first quarter of 2019, according to China Customs spokesperson Li Kuiwen. But soybean exports to China were dramatically below average in 2019.

Current soybean exports are a small portion of the promised purchases outlined in the trade agreement. Although the trade agreement includes clauses covering unforeseen circumstances that would trigger adjustments, through mid-April, no formal request for renegotiation has been made by either China or the U.S.

Unfortunately, the lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the U.S.-China trade agreement is still largely unknown.

“We certainly hope exports will increase in response to this agreement,” Kuehl adds. “But uncertainty is reflected in soybean prices. Trade is not a like a light switch that can be flipped off and then back on. While we’ve been out of the game, others have stepped into the markets we held in China.”

That’s exactly why USSEC is maintaining relationships with Chinese buyers, according to Sutter.

“Throughout the U.S.-China trade talks, our partnerships in China remained strong,” he says. “We have continued to hold meetings with Chinese importers in both the U.S. and China. In early January 2020, USSEC had a delegation of farmers in Shanghai.”

With travel restrictions now in place, USSEC hasn’t allowed those relationships to languish. USSEC implemented video conferencing and other technologies to facilitate stakeholder interaction, support and access.

In April, USSEC hosted a two-day virtual conference with 1,600 U.S. soy customers and soybean industry representatives from China and more than 80 other countries.

USMCA

The agreement with Mexico and Canada that modernized the 25-year-old NAFTA agreement creates much more certainty than the preliminary China agreement.

“Mexico and Canada are some of the largest markets for U.S. soy products,” says Sutter. “The importance of USMCA can’t be understated.”

Kuehl agrees. “USMCA stabilizes relations with two of our largest trading partners,” he says. “While it doesn’t change the playing field for soy, it gives certainty to business as usual.”

According to Sutter, Mexico became the second-largest market for whole soybeans and soybean oil from the U.S. The Mexican livestock industry is U.S. soy’s second-largest customer. He says it’s a growth market because of increasing demand for meat, poultry and eggs due to population and economic growth inside Mexico.

In addition, Sutter notes that Canada is also an important meal and oil customer, as well as being the largest, albeit small, export market for U.S. biodiesel.

Additional Opportunities

Mainstream media headlines continue to mention potential trade agreements, and during the uncertainty of the past couple years, other markets have become increasingly important.

“Soy needs the U.S. to lean into expanding market access for farmers,” Kuehl says. “It takes time to see the benefits from trade agreements, so it’s critically important that we are working on them now.”

That mindset has driven recent USSEC efforts, according to Sutter.

“USSEC is working tirelessly to provide stability by building demand and expanding global market access for U.S. soy products,” he says. “As a part of these efforts, we launched the ‘What It Takes’ initiative in July 2018.”

Sutter explains “What It Takes” builds on existing relationships and invests in new ones in emerging markets. It focuses on

understanding end users’ needs and meeting them. The U.S. can provide higher protein, essential amino acids, high oleic soybean oil and proof soybeans are grown sustainably.

USSEC also held more than a dozen “Experience Today’s U.S. Soy Advantage” events around the world to share U.S. soy product advantages and availability where relationships have already started.

“We’ve seen growth in the European Union, Middle East/North Africa and Southeast Asia,” he says. “We’re working hard in emerging markets such as India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nigeria, Algeria and Myanmar.”

With both the trade agreements and efforts to build new markets, Kuehl describes three potential short-term outlooks for soybean trade.

“If China fulfills Phase One commitments, soy exports would increase,” he says. “Or, China may not increase imports, but a Phase Two agreement could reduce tariffs, which would increase the competitiveness of U.S. soy and trade with China.”

But Kuehl acknowledges that the current status quo is also a possibility.

“Regardless, the dedication of U.S. soybean farmers to supplying high-quality soy to partners has never wavered,” says Sutter. “They stand ready to supply sustainable, high-quality soy to our trade partners where markets are growing due to demand, trade agreements and relationship cultivation. U.S. soybean production remains switched on.”