Unlocking Potential with Lock and Dam #25

Over the last century, countless gallons of water have moved billions of tons of commodities, including U.S. soybeans, down the Mississippi River. For more than 80 of those years, every barge has passed through Lock and Dam #25.

And this critical piece of infrastructure is ready for some 21st century updates.

The lock and dam system hasn’t been modernized since its construction in 1939. This is causing significant delays due to the single lock chambers that raise and lower vessels moving from one water level to another. The lock chambers are only 600 feet long, while most barges are double that length. This requires barges to “double lock,” significantly slowing delivery of U.S. commodities.

“A reliable and efficient transportation system is one of U.S. Soy’s biggest advantages over our competitors,” says Meagan Kaiser, soy checkoff vice chair and Missouri soybean grower. “Unfortunately, that system is deteriorating and straining our export system, putting the reliability and predictability of delivering soy to our global customers at risk. Soybean farmers understand this, which is why the checkoff is working to modernize and maintain the infrastructure. This will keep us competitive and create and return value to U.S. soybean farmers.”

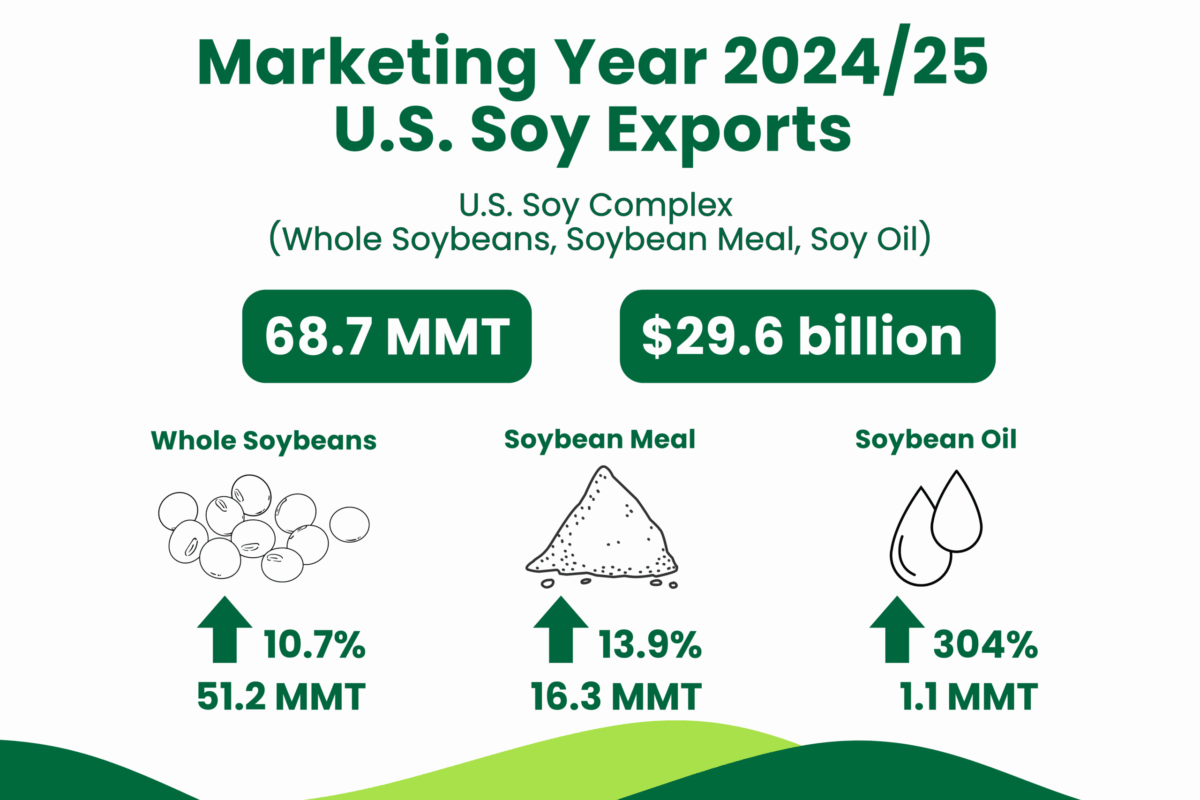

During the last marketing year, 61.65 million metric tons of U.S. soybeans left the farm to travel around the world, going to various countries for various uses. Any slowdown along the way can affect their competitiveness. As input costs continue to rise, that’s something U.S. farmers can’t afford.

“It’s not a good look if we’re unable to get our soybeans to customers,” says Matt Gast, a soy checkoff farmer-leader who grows soybeans in North Dakota. “We can invest in new markets to boost demand for our crop, but if we can’t provide the beans because our infrastructure lacks the updates we need, it’s all for naught.”

According to the Waterways Council, Lock and Dam #25 accommodates 200 million bushels of soybeans annually. An outage at this facility would cost nearly $1.6 billion and increase truck traffic by more than 500,000 trips annually. Additionally, a 2016 report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture warned that aggregate economic activity related to grain barge transportation would decline by 40% — $933 million — if Lock and Dam #25 was closed from September to November.

“Our soybeans automatically become less desirable if we can’t get them where they need to be on time. That means our customers would start to look for soybeans from other origins, which would directly affect our bottom line on the farm,” says Gast.

The soy checkoff understands this challenge and joined with the Soy Transportation Coalition, Illinois Soybean Association, Iowa Soybean Association, Minnesota Soybean Research and Promotion Council, Missouri Soybean Merchandising Council and Iowa Corn Promotion Board to commit $1 million to offset pre-engineering and design work expenses required to bring Lock and Dam #25 into the 21st century.

The agriculture community isn’t the only one dedicated to modernizing Lock and Dam #25. In January, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers released a detailed list of projects earmarked to receive funding in 2022 under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Lock and Dam #25 will receive $732 million for improvements.

These funds will go toward building a new, larger lock chamber adjacent to the existing lock chamber. This will enable a typical 15-barge tow — transporting over 800,000 bushels of soybeans or corn — to transit the lock in a single pass, which takes between 30 and 45 minutes, compared to the two hours it currently takes to double lock.

Lock and Dam #25 is the first project under the Navigation and Ecosystem Sustainability Program to receive funding. NESP is a long-term program, authorized by Congress, to improve and restore the Upper Mississippi River System. Primary opportunities for improvement include reducing commercial traffic delays while restoring, protecting and enhancing the environment.

In addition to Lock and Dam #25, there are seven other locks specified by NESP for improvements, along with other critical infrastructure like the St. Lawrence Seaway, another stop on the Mississippi River that helps U.S. soybeans get where they need to go.

Sailing on St. Lawrence

The St. Lawrence Seaway reaches 2,340 miles from the Atlantic Ocean to the head of the Great Lakes in Duluth, Minnesota, and currently carries less than 2% of U.S. soybean exports. A recent agreement between the Soy Transportation Coalition (STC) and the St. Lawrence Seaway Management Corporation (SLSMC) incentivizes more agricultural shippers to use the route through SLSMC’s Gateway Incentive Program.

“Whether farmers’ crops go to the Pacific Northwest, down the Mississippi River or on the St. Lawrence Seaway, it’s just vital for all U.S. soybean farmers that we have these avenues for our crop to travel,” says Gast.

As demand for soybeans continues to grow around the world, supply chain stakeholders need options to meet demand quickly and efficiently. This agreement delivers on that need. For the soy checkoff, strategic partnerships like this one ensure U.S. soybeans continue to benefit from the country’s top-notch infrastructure system.

“Infrastructure is a big deal for not only U.S. soybeans, but all commodities, and it’s great to see so much collaboration to make improvements,” says Gast. “From the national soy checkoff to state soybean boards and all the partnerships in between, we all see the potential our infrastructure system has, and we’re going to work together to improve it.”